Reminiscences of his Early Life

by Charles Howard Hopkins

| First Article: Prelude Nebraska Kansas Kentucky - The Mountains Kentucky - Berea |

Second Article: Our Life in Kearney, Nebraska Third Article: Kansas |

Fourth Article: Additional Data on the Hopkins Family Fifth Article: Remembrances of the Hopkins Family and the Times in Which They Lived |

Notes on these articles |

PRELUDE

The Hopkins family had its beginnings in America in Haddonfield, New Jersey during William Penn's time. The town of Haddonfield was named for Elizabeth Haddon, immortalized in Longfellow's poem "Elizabeth". She brot her nephew, Ebenezer Hopkins from England, and built him a house, which is still standing, and is occupied by the family of a former New Jersey governor, Mr. Driscoll. I walked by this house when I was starting home from a trip to an American Chemical Society meeting in Atlantic City. As it's ties with William Penn indicate, this was a Quaker settlement, and the Hopkins family were Quakers. Two generations later Hezekiah Hopkins left New Jersey for the frontier, which was then Ohio. His son, William, moved further on to Indiana, where he founded the town of Pennville. A letter from my Uncle Ed, my father's oldest brother, said that William used to lead trade caravans thru Indian territory to Ft. Wayne and to Cincinnati. Because he was a Quaker and had the trust and respect of the Indians, he was much sought after as a guide and go-between by these traders and others.

One of William's sons was my grandfather. He settled down to the life of a farmer. He married a Welsh-Irish girl named Mary Ann Daily, who was the most saintly woman I have ever known. My father, Arthur H. was their fourth child. Life was hard on the farm, and he had to help support the family from an early age, and he said his formal education probably didn't go beyond the third or fourth grade. Despite that, I must admit he could write better than I can, seldom or never misspelled a word, and his mind remained clear and his judgments beyond reproach until his death at age ninety six. Altho my grandfather didn't fight in the Civil war, he was active in the Underground Railroad, helping escaped slaves to a safe haven in Canada. He later disagreed with some of the Quaker beliefs and became a Baptist. However, the early Quaker influence in our family has remained strong, and has been incorporated into our family traditions and values.

As my father reached early manhood he became acquainted with the oil industry by doing a brief stint in the new oil fields in Indiana. Sometime later he participated in the famous run into the Cherokee Strip in what would become Oklahoma, but didn't appear to like what he saw, and returned to Indiana. While there, he met my mother, who was then Belle Boone-Greene, the adopted daughter of a Baptist minister.

My mother was born Hattie Belle Boone. The family claimed direct descent from Daniel Boone, but had no actual records verifying the relationship. Her mother died while she was still quite young, and her father "farmed" out his family. The Reverend Greene adopted mama. He was not always a Baptist minister. He had served in the U.S. Cavalry under General George Custer, and as his good fortune would have it, his contingent had been assigned to a different mission before the day the Northern Cheyenne and the Sioux evened scores with General Custer at the little Big Horn. Grandpa Greene used to regale us children with tales of his escapades as a cavalryman, and of what a ruthless and brutal disciplinarian Custer was toward his own men. According to Grandpa Greene, Custer's men hated him.

NEBRASKA

After marriage, my father wanted to establish a farm of his own, in what was still pretty much virgin land in Nebraska. He and mama moved to Buffalo county in Nebraska, north of the town of Gibbon. He worked for a farmer there, presumably with the idea of saving enough in time to make a down payment on a farm of his own. I was born while they still lived there. I am not sure whether my older sister, Helen, was born there or in Indiana. But mama began having health problems there, and they became so serious that he had to leave the farm and move to the County seat, Kearney, about fifteen miles West of Gibbon, where mama could get adequate care.

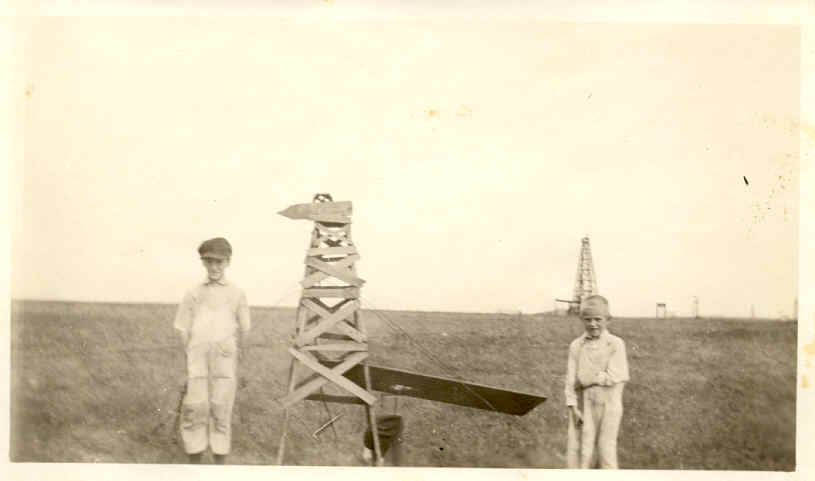

Picture of Howard and Helen Hopkins as children |

Our home in Kearney was in the northwest corner of town. It had a large barn, and possibly other smaller outhouses (I don't remember), and two large lots on the east and west sides of the house, which papa used for gardening. He used the east garden for the usual garden vegetables, and the west garden for those crops which required more land, such as corn, squash and pole beans. He had chickens, one or more cows, and sometimes hogs. He had a sturdy team, Kit and Fleet, which were his stock in trade for work around Kearney. I remember one Autumn when he butchered a hog, and the huge cast iron kettle used for scalding it in, so the bristles could be scraped off easily. The fat was rendered out, and pressed from the cracklings with a lard press. Much of the meat was ground up and seasoned as sausage, rolled into golf ball-sized units and baked. The sausage was then stored in stone crocks in its own grease, and in this condition it kept safely until ready for use. Some foods, like corn and apples, were dried for later use, and were cured against spoilage via a sulfur candle. (I remember how good they were, dried). Ruth, Donnie and Ralph were born while we lived there.

Papa's means of livelihood in Kearney was in whatever hauling jobs he could pick up, and in a rural community, there were relatively few. I remember vividly one New Year's Day, when an ice storm had settled over the city, and all activity was at a standstill, the manager of the local coal and lumber company phoned that the military academy a few miles east of town was out of coal, and the students were freezing. He couldn't get any of the other haulers to go out into that ice storm to deliver the coal, and he asked papa if he would do it. For the sake of the family he delivered the coal; but I'll never forget seeing him upon his return. His clothes were covered with ice, and icicles were hanging from his nose and mustache.

Some of his hauling experiences were somewhat of a lark for me. One summer, when I was about eight years old, papa had a contract with the same lumber company to fill a hopper car with sand from the Platte river. That was a high point of my life, for he took me along, and with my little shovel I helped mightily to fill the wagon. He drove down into the river bed at the Kearney end of the wooden bridge, which was reputed to be a mile long. The Platte lived up to its reputation for being a mile wide and an inch deep. The water lay in isolated rivulets, so the sand was plentiful, and of the finest quality. When papa drove his wagon onto the scales for weighing, I must have been quite a pest, because both the station master and papa promised me that if I would sit quietly on the wagon seat while the load was being weighed in, my weight would be allowed on papa's total. Boy, was I ever proud of my contribution.

There were many pleasant memories of the happier side of our lives in Kearney. When Ralph was still a baby, papa used to enjoy letting him play with his handlebar mustache. One night Ralph grabbed both handles - and pulled! That was the end of that game!

When papa came home from work on many evenings, a garrulous old neighbor used to meet him, and engage him in endless conversations while papa was taking care of the horses and putting up the harness. He would stand holding his hands stiffly behind his back, and everything that papa said, he would agree with. He would nod his head from the waist up, and vehemently exclaim, "EGGS-ZACTLY!!" Us kids were frequent amused spectators at these events, but they must have made more impression on Donnie than on the rest of us. He must have been around five years old at the time. One evening when we were doing our little chores around the barnyard, Donnie was gathering the day's eggs. He was gathering them in a basket, and he set the basket down to look in another nest, when a dog we had at the time picked the basket up by the handle and made off with it. Donnie ran after the dog, screaming "EGG! EGG! EGG-ZACTLY!"

Once when Donnie came home from school around Christmastime, mama asked him what they did at school that day. He said they sang some Christmas songs. Mama asked him what songs they sang, and he said, "Hark the Harold Angels Sing", and "Little Tommy Bethlehem".

Us kids used to enjoy playing in the barn, especially in the haymow. From the loading door in the back of the mow we used to enjoy jumping down into a pile of manure (mostly straw). It was great fun except for the baths we had to take afterward. We entered the mow via a ladder inside the barn, and pitched hay down for the horses and cow(s). But the hay around the entrance ladder was worn smooth, and care had to be taken to keep from getting too close to the edge, or one could suddenly find one's self tobogganing down onto the barn floor. That is exactly what Ruth did - with a pitchfork in her hand! Fortunately for her, she was not impaled on the fork. Who says there are no guardian angels?

One Christmas mama and papa got us children the most wonderful Christmas present - a beautiful little wagon, one of the deluxe kind. I believe it was the only gift they got us, and I remember distinctly that they didn't get each other any presents, so they could get us a present we could enjoy and remember.

One day papa loaded the entire family into his spring wagon and took us to a cherry orchard a few miles west of town, and we spent one glorious day picking cherries and picnicking. We picked them on the shares, and we got to keep half of what we picked, plus the modest amount our parents permitted us to stowaway.

Not all the memories of life in Kearney were pleasant, however. That wouldn't be life if they were. First, mama's health deteriorated, and she finally had to have an operation on her left kidney. From that time on, she had to live with a tube draining from her kidney into a pad. The second tragedy was that Donnie caught pneumonia, and if Grandma hadn't spent day after day rocking him in a cold room, he may not have survived. The third, and worst tragedy was the sickness and death of Helen. She had been misdiagnosed as having scarletina, but it was discovered too late that she had Bright's disease.

Editor's Note: Bright's disease is a chronic disease of the kidneys.

Kearney was a perfect example of a grid-structured town. Streets ran east-west, and avenues ran north-south. It was the county seat of Buffalo county, and was completely agriculture-oriented, with no industries that I remember. Hence, it provided a poor base of support to any man who had to earn a living by common labor. Papa supplemented his income from hauling jobs by raising a large portion of our food in his large gardens, and by keeping one or more cows, some chickens, and sometimes raising a few hogs. He rented a field near the Kearney lake to grow alfalfa for his horses and cows, and he raised corn for the hogs on the west garden plot.

The topography of that part of Nebraska was flat, and I remember when the teacher asked her class to draw their conceptions of a mountain, my picture resembled an inverted ice cream cone. I also had no idea what a rock looked like, as there were no rocks larger than gravel around Kearney.

Summers were pleasant in Nebraska, altho I remember one occasion when hailstones as large as baseballs lay thickly in our yard. The winters, on the other hand, were appalling. One winter we had a blizzard that lasted for days, and when it was over, papa had to tunnel from the house to get out to the barn to care for his livestock. When we kids finally got out, we found the snow had drifted even with the eaves of the house on the north and west sides. We could take our sled clear up to the chimney at the peak of the house and slide back down. That was the nearest thing to a hill we experienced in Nebraska.

The people of Kearney, like most rural or small town people, were warm and generous. The doctor who operated on mama allowed the family to pay as much of the bill as we were able with milk and eggs. But eventually papa had to leave Kearney to find enough work to maintain his family. Uncle Charlie, Grandma and Aunt Emma had gone to the new and prolific oil field near Eldorado, Kansas, and they persuaded papa to come down, where they were sure he would find work. So he packed his most necessary needs, plus some things he wouldn't have paid to have shipped down, into his wagon, and with Trixie, our collie, he drove the four hundred miles or so down to Kansas. It was an open wagon, the weather was bitter, and he said he suffered more on that trip than on any other he had taken. After he got there he had no place to stay except the tent he took along. One day, while he was at work, some thief stole his valuable collection of Indian arrowheads, spear points, hammers, pipes, etc., which he had saved from plowing in Indiana and Nebraska. But he got work as a pumper, a job he was to follow for the rest of his working life in oil fields from Kentucky to Wyoming.

Howard Hopkins

March 1, 1991.

KANSAS

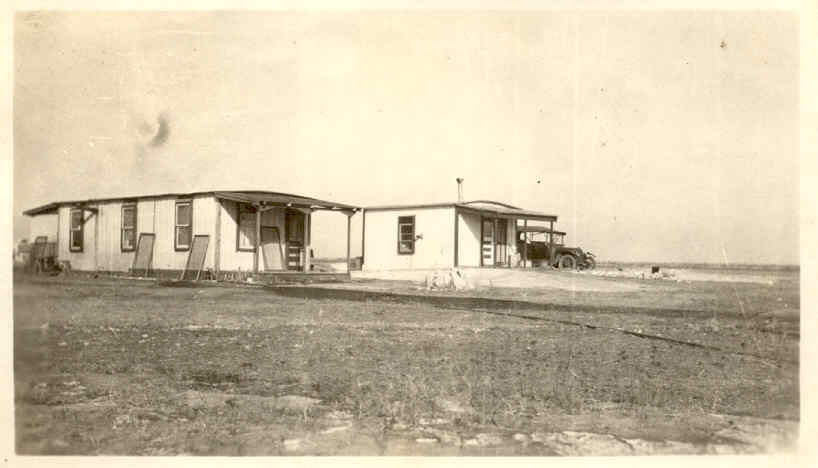

Picture of Charles, Emma, Mary Ann, & Arthur Hopkins |

It took awhile before the oil company papa worked for could provide housing for the influx of people needed to man the field, but eventually they provided a small (2- or 3-room) clapboard house, and papa sent for his family to join him. If we thot Nebraska was flat, then that part of Kansas was, if that were possible, even flatter. But I did learn what rock looked like - not stones, but rock. Limestone bedrock was never more than a few inches below the surface of the ground. The Walnut river, unlike the Platte, actually had water in it, altho most of the time it had a scum of oil on the surface, plus discarded salt water from the wells. Derricks were everywhere, even, eventually, in our own front yard. Our house was primitive by almost any standards, and we supplemented it with a tent in the back, which we used mostly for storage.

We lived thru two tornadoes there. During the first one, mama went into the tent to try to batten things down, when the tent collapsed, the ridge-pole almost knocking her out. Every derrick around us was flattened in that storm, and a total of 365 derricks were destroyed fieldwide. During the second tornado the house next to ours was set catty-cornered on its foundation.

In Kansas we met, for the first time, our cousins from Uncle Will's family. The boys were James and Charles, roughly my own age, with their older sisters, Gladys and Ethel. We boys had many good times together, hunting and trying to trap rabbits (I don't remember ever catching one), and learning to swim.

Uncle Charlie was also a pumper in that field, and one of the units he operated was a power house, where a single large Superior gas engine operated several shallow wells by rodline. He had a crude home-made chair in the power house that was wired so that when placed close to the large belt going from the engine to the enormous wheel that operated the rodlines, a person sitting in the chair would get a spine-tingling shock. Us kids enjoyed that. He also had a gas burner on the floor several feet away from the big wheel, surrounded by bricks, that he used to light on winter days to warm up by while on his rounds. He allowed us kids to gather around it from time to time. On one occasion Ruth, Donnie and I were gathered around the fire when the massive piston rod of the engine broke close to the piston. The momentum of the flywheels on the engine kept the piston rod flailing until it hammered huge chunks of metal out of the engine and catapulted them all around the power house. All around, that is, except where us kids were, altho some chunks landed within three feet of us.

Picture of Howard Hopkins (left) and toy oil derrick |

Another escapade involved Ruth alone. Some of the oil receiving tanks were erected so hurriedly that they had no tops on them. A catwalk of a 2"x10" plank was laid across the top of the open tank, and that is what the pumper used in case he had occasion to cross the top of the tank. One day mama missed Ruth being around, and when she started looking for her, there she was, blissfully walking across the catwalk. Mama nearly had heart failure, but didn't dare distract Ruth in that precarious situation, lest she fall off into the tank. So she went to the tank as calmly as possible, and told Ruth something to the effect that it was time to quit playing around the tank and come home. Footnote: If Ruth had fallen into the tank unnoticed, she would have sunk immediately to the bottom, and nobody would have known what had become of her.

There was another scenario in which Donnie, Ruth and I engaged in. The derrickmen were building a derrick in what one might whimsically call our front yard. It took several days, and at the end of each day's work they left everything lie in the open. One evening after supper Donnie, Ruth and I clambered onto the floor of the derrick and started gathering the loose nails the carpenters had scattered around. They had a nail bucket on the end of a rope which went over the crown pulley, some 72 feet above the floor, in which they hoisted nails up to the workmen in the top of the derrick. We persuaded Donnie to climb into the bucket, and Ruth and I began hoisting him up. He was delighted; but he was small and light, and before long the weight of the rope on the down side outweighed him, and he began a slow ascent toward the top of the derrick, while Ruth and I frantically pushed on the rope in vain. Then Ruth started screaming, and papa and uncle Charlie came rushing out of their houses to see what the trouble was. By that time Donnie was up to the crown pulley, enjoying every minute of it. But not papa and uncle Charlie, nor mama and the other women in the collective family, who had joined the melee. Since papa was afraid of heights, it fell to uncle Charlie to climb the derrick and start Donnie on his descent, while papa tended the other end of the rope to control the gathering speed. Everybody was so thankful to get Donnie back down safely again, they plumb forgot to whale the daylights out of Ruth and me.

One of the ironies of living in an oilfield was that the company supplied coal to its employees for use when gas flow was disrupted. They also supplied lean-to type sheds to store the coal in. One frosty December morning I decided to climb on top of the coal shed. First I looked over the upper edge, then turned around and looked over the lower edge. I saw more than I had bargained for; I started sliding, and there was nothing I could grab to stop me. So I spilled down over the back side of the shed - and my nose hit a sawhorse on the way down. The realization dawned quickly what a stupid thing I had just done, and I slunk humiliated into the house, and nursed my injured nose behind the living room stove unnoticed all that day. I didn't know until I was a sophomore in college, when the college doctor told me during the pre-admission examination that I had broken it.

During the winter of 1918 the terrible epidemic of influenza swept the nation, and it didn't spare the inhabitants of the Eldorado oil field. Every member of our collective family was down with it except papa, and he had to take care of his lease, his family, uncle Charlie's family and aunt Alice's family, (We all lived in a cluster of houses called a "camp"). But everyone survived, thanks to papa, who miraculously escaped.

The Eldorado oil field was said to have been the field that fueled this country's drive in World War I. So maybe it was no coincidence that both of them wound down together. In the Spring of 1919 layoffs began thruout the field, and men began to cast about anxiously for their next jobs. The Hopkins family cluster knew they wouldn't be spared, so when the field foreman of the company they worked for was notified he was being transferred to a new oil field deep in the mountains of Kentucky, he asked papa, uncle Charlie and uncle Will whether they would be interested in working there. All three accepted, and Aunt Alice and her husband returned to Texas. Housing was nearly non-existent in Kentucky, so provision had to be made for the family until a house could be provided.

It seems that mama's father had remarried, and his widow was running a boarding house in her home in Ft. Wayne, Indiana. Arrangements were made with her to board the family until the end of the next school year, while papa got established in Kentucky, and a decent house provided for his family. And so the Kansas part of our story was completed.

KENTUCKY - THE MOUNTAINS

The transition from the flatlands of Nebraska and Kansas, and the urbanity of Ft. Wayne, to the heavily-wooded hills of Eastern Kentucky was a spectacular event, especially to four children eager for new adventures. Partially unexpected was the even greater transition to a new and unfamiliar culture, and indeed into a different era.

The mountains of Eastern Kentucky were unlike those of the Big Smokies to the east, or the Rockies to the west. That area has been described as a deeply-eroded plateau, with chasms, called hollows by the natives, following creeks, many of them several miles long. The whole area was densely forested with both pines and a wide assortment of hardwoods, grapevines, sassafras and other shrubs, and such exotic wildflowers as rhododendron, the equally beautiful mountain laurel, tulip poplars, etc. Spice bushes like bay laurel abounded there, and blackberries proliferated; we used to enjoy looking for wintergreen in clearings. Several kinds if hickory nuts grew wild, also black walnuts and butternuts. Chestnuts were abundant, as the great chestnut blight that wiped out chestnut trees nationwide had not yet appeared. Bears and panthers had been all but eliminated, but many bobcats persisted, as well as the more common foxes, racoons, possums, skunks, and of course a variety of snakes. Natural springs were common and widespread. They were the source of water, not only for livestock, but for family use as well.

The mountain people were predominantly of Scotch-Irish descent, and poured into that region following the opening of the Cumberland Gap by Daniel Boone. They brot with them their traditions and customs from the old country. The Kentucky hill country proved ideal for preserving their culture, and the era that spawned it, as it effectively locked them in and locked external influences out. Cracks appeared in the "fortress" with the coming of the big coal companies, and later on with the coming of the oil companies. This was followed later with the large-scale building of roads thruout the mountain area, followed by more and better schools.

The social structure of the original Scotch-Irish people was built around the greater family, or clan. One of the deep-seated traditions of this culture was the famous clan warfare, or feuding between clans. Often the original reason for the start of a feud was long-forgotten, but the feud still carried on. As could be expected, these people were fiercely independent, and did not take kindly to too much interference in their personal affairs by the governing bodies. This infringement on their right to turn their corn crop into "white mule" made moonshining a popular pastime thruout the region.

Their language seemed peculiar to us, and took quite a bit of getting used to. For instance, they called our household goods "plunder", and said the railhead where it was put off was "a right smart fur ways from here". Many of their customs also struck us as peculiar; for instance, when a husband and wife went anywhere, the wife never walked beside her husband, but a respectful space behind him. Their farming equipment was primitive; the plow was a blade just barely able to scratch the surface of the soil. Altho they lived humbly, they raised most of the things necessary for their subsistence. Us "furriners", as they called us, were accepted with great reserve at first, but as familiarity between the two groups grew, many of the native people proved to be very warm, open friends. There were exceptions, of course, but more about them later. The houses the people lived in were mostly crude by our standards, but were probably adequate for the circumstances in which they lived. The predominant religion was what we called "Holy Roller", and the musical instrument of choice was the 5-string banjo. Their music was what they brot over from the old country, plus what they composed within their confines, and therefore had a distinct regional flavor to it.

Picture of the Hopkins families in Kentucky |

When Uncle Charlie, Uncle Will and papa left Kansas for Kentucky, Uncle Charlie and Uncle Will went in as foremen in different parts of the new field, and papa went in as a pumper on Uncle Charlie's lease. The company had already provided new and comfortable houses for Uncle Charlie and Uncle Will, but had not yet built one for papa and his family. Hence the detour of his family to Ft. Wayne until his house was finished, and our school year was over. When the family finally came down to its new home, we disembarked at Torrant, the railhead where the heavy equipment destined for the field was unloaded. From Torrant to our new home was seven miles over some of the worst road I've ever seen. Our house set back a few yards south of the road, and from there we had a front seat for everything that came and went over that road. Papa eventually fenced in the yard and his inevitable garden space.

The house where Uncle Charlie, Aunt Emma and Grandma lived was about 150 yards south of us. About 50 yards back of them was the drop-off that marked the head of Hell Creek Hollow, a miles-long chasm with multiple sidearms, that was part of Uncle Charlie's lease. Just over the rim of the cliff going down into the hollow was a cave, and in it was the spring where Uncle Charlie's family and papa's family got the water for our daily needs. It remained clear and cool the year round, and papa and Uncle Charlie scooped out and cemented in a basin big enough to collect sufficient water for both of our needs. We carried our water from there, usually two pails at a time.

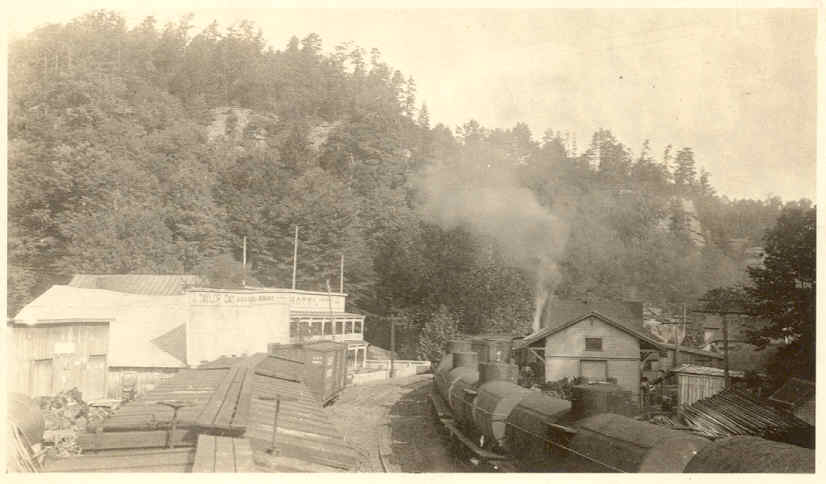

Zoe, Kentucky |

About a mile east of us was what passed for the local school. It also doubled as a meeting place for the church people. Just before we came down there, one of the smouldering feuds erupted during one of the "meetings", and one of the men was shot dead. A little farther on was the town of Zoe, containing a single general store and postoffice. I just wish that store could have been preserved for posterity. Just picture a typical country store, and then overlay it with the demands of an oilfield frontier, and it may give you some idea of what it was like. We got all our mail and most of our groceries from there, and we usually reached it via a footpath, as it was usually better than the road.

Torrent, Kentucky |

The road ran from the railhead at Torrent to the County seat of Lee County, Beatyville. That portion of the road over which the heavy equipment for the oilfield was hauled was always in abominable condition, due largely to the springs that could not be avoided when the road was laid out. Small mudholes quickly became large ones, and in one in which more than one spring was involved, at the "town" of Zachariah, the mudhole was a quarter mile long, and was so deep that a team of six mules was drowned in it, trying to haul a wagon loaded with a boiler thru. They brot in a string of oxen and snaked the wagon out, then hitched the oxen onto it, and they pulled it thru. That will give you an idea of some of the difficulties encountered in maintaining an oi1field in this difficult terrain.

Another "road" incident that still remains vividly in my memory involves the hauling of nitroglycerine, which was used to "shoot" wells to fracture the rock structure at the bottom of the holes. It was usually stored in "magazines", small sheds tucked far back in the woods. When needed, a wagon would load up and take it to the desired location. Sometimes the cans were stored over an extended time before any was needed. Naturally, it was difficult to find men who were willing to take such a risky job. But premium pay was able to lure some men to do such work. Being conscious of the extreme risks involved, especially over the oilfield roads, they fortified themselves for the task by getting rip-roaring drunk.

One day some of us kids were playing in our front yard when a "nitro" wagon rolled slowly by. It was pulled by four mules and two lead horses. It was very evident that the two men on the wagon were "fortified". But as the wagon passed by, I noticed liquid dripping from the back end of the wagon. I guessed what it probably was, but there was nothing I could do about it, so I let it pass. About two hours later a tremendous blast toward the west shook the earth and rattled some dishes in the cupboard. When papa arrived home, he, mama, Ruth and I walked about three miles west, and came upon the spot where the nitro wagon had blown up. They had been carrying six hundred quarts of nitroglycerine, one or more of the cans had been leaking, and they were on a portion of the road where ledges of rock outcropped across the road. A sudden sharp jolt was probably all it took. It excavated a hole in the ground about eight feet deep and perhaps twenty feet across. The force of the blast veered off to the east, stripping the forest of leaves and small branches for a considerable distance. Searchers were able to find a cigar box full of mixed human and mule remains for burial.

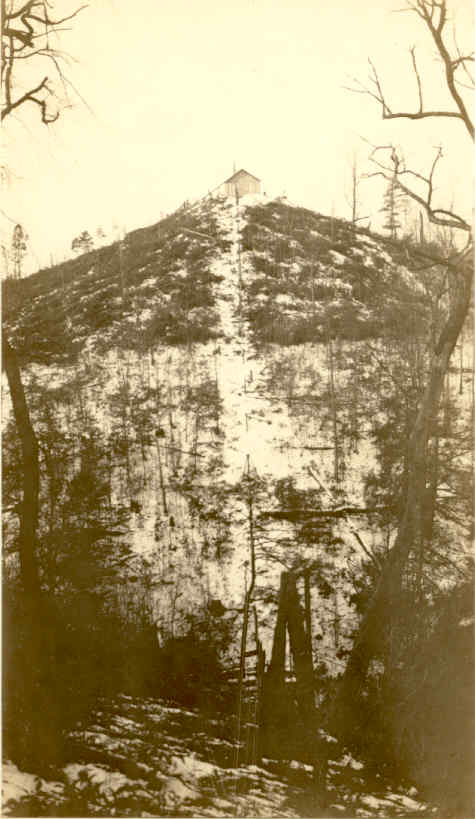

Arthur Hopkins' powerhouse |

Papa's power house was situated on top of a relatively steep hill across the road from our house. Rodlines passed from the powerhouse as far as three miles to the east, and a mile and a half to the west, as well as several to the south. These provided the power that pumped the wells. There were none toward the north, as another deep hollow opened up to the north of the power house. The extreme stress of these distances, plus the difficult terrain, caused papa to become quite lame, and he always had to make his rounds with a cane. But the cool, green, silent hollow behind his power house was a favorite place for us kids to explore. We were often joined by Uncle Will's boys, our cousins James and Charles.

Blackberry picking time was always greeted joyfully by us children. On one such venture, to an especially productive patch about three miles from home, a storm came up while we were picking. We decided to leave before it started to rain, and covered the first two miles before it let loose. We paused briefly under a large tree, then Ralph and I decided we were getting wet anyway, so we left, and Ruth and Donnie decided to stay. Ralph and I had gone less than one hundred yards when Ruth and Donnie decided they had better join us. When they had covered about half the distance to us, the lightning hit the tree they had been standing under and split it wide open.

Along with James and Charles, Donnie and I found the scant remains of a moonshine still in an open cave on one of our explorations. On another one, we intended to explore a new (to us) area. We reached a fence and were just in the act of crawling over, when a shot came whistling over our heads. The exploration ended right there.

One day while we children were playing in the yard, a native boy of sixteen showed up and made our acquaintance. On this and several other appearances, he tried to play with us, but didn't seem to know how. We found that he was a derelict; either his parents were dead or remained drunk, and he spent his time shuffling among relatives, none of whom seemed to care for him or try to control him. He normally carried a .38 caliber pistol, but we didn't think too much about that. But soon he tried bullying us, and one day when that failed to produce results, he confronted me in the middle of the road and drew his pistol and pointed it at me. I knew I didn't dare to knuckle under to him, but I didn't know what he might do. So I just stood there and faced him down. After some very long moments he lowered his gun and walked away. He didn't surface again for a couple of weeks, and then it was to chop one of papa's pipelines in two with a double-bitted axe.

Another unpleasantness occurred while we were there, but this time to Uncle Charlie. One day he found it necessary to fire one of his workers. That night two or three shots from a highpowered rifle crashed into his house. Fortunately, none of the three family members was hit, and the incident was not repeated. But the man stayed fired, and Uncle Charlie purchased a .25-.20 rifle against further such occurrences.

As I noted earlier, most of the heavy hauling was done with mules or oxen. When the task was too difficult for mules, oxen were used, and they were the mainstay for getting the job done. I have seen strings of as many as twenty-two oxen hitched to one wagon.

Us children really got to know and adore Grandma Hopkins while we lived in Kentucky. She was the gentlest, most loving person I have ever known, and she could make the best soft ginger cookies that have ever been made, or ever will be.

Occasionally it became necessary to purchase items not available at the store in Zoe, so we had to travel to a town on the railroad. Torrent was too far from where we lived, and was a perpetual mudhole, but there was a town further down on the line, named Fincastle, that was four miles or so from home. It could be reached from there only by footpath, thru densely wooded country, and thru a defile in the cliff down into the valley where Fincastle was located. On one such journey to Fincastle the creek in the valley was in flood, so we paused to watch a group of native teenagers frolicking in the water. Gazing upstream, I spotted two water snakes fully seven feet long coming down with the flood waters. I yelled to the teenagers, warning them of the danger bearing down on them. Instead of getting out, they grabbed the snakes and had a great time playing with them before they released them to continue on downstream.

Inevitably, the question of school arose before the summer was over. By some good fortune Uncle Will and his wife learned about a small boarding school in the small town of Stanton, located on the L&N about halfway up toward Winchester. They arranged to enroll their two daughters, Gladys and Ethel, and James and Charles in the school, and suggested to papa and mama that they investigate the chances of enrolling us children. Ralph was still too young to be accepted, but they did enroll Donnie, Ruth and I. Going to the local school was out of the question, as the local hoodlums kept its windows shot out; and they understandably had difficulty in getting a teacher to take the job, or to remain if it was taken.

The school at Stanton was a surprisingly high quality school for that region. The teachers were excellent, and the atmosphere was conducive to learning. The girls were housed in a nice brick dormitory, with the ground floor containing the dining room for both boys and girls. The boys were housed in a large two-story home, run by a man and his wife. Ruth and I spent the entire school year there, but an infection of boils swept the boys' dormitory, and Donnie contracted such a bad case of them that he had to return home.

I could recount many small incidents that occurred while we were there, but I will limit it to just a few. I cite one incident as a contrast to the way things were done then, vs today's scene. One of the town's main streets was in need of repairing and widening, so the townspeople pitched in and did the work themselves, gratis.

Stanton was one of the only places where I've lived where I couldn't orient myself with the directions. In a semi-bog field, what to me was northeast of town was a grove of hazel nut bushes or trees. We used to like to go there and load our pockets with those delicious nuts. Those were the only hazel nuts I've ever seen growing.

Once when James, Charles and I were out exploring the countryside, we followed the railroad to where it crossed Kentucky's Red River, a mile or so north of town. Out of pure boyish adventuresomeness, we crossed the bridge on the ties, and were about halfway back, when a warning whistle told us a train was approaching from the north. Time was too short to make it to the south bank, so we sat on the tie ends, braced our legs under the tracks, and leaned back with all our might. The train rolled right over us, and fortunately for us, did not spew steam and hot water over us in passing.

Us boys joined the Boy Scout troupe while we were in school there, and I still remember the fine scoutmaster we had. He planned to take us on a camping trip one time, and was to leave about the middle of the afternoon. But James and I had some small jobs and couldn't leave with the troupe. So the scoutmaster gave us detailed instructions on how to reach them, and we left when our jobs were finished. Darkness fell some time before we reached the camp site, and as we approached it, we passed thru an abandoned peach orchard. We didn't have a light, but we found the ground littered with peaches. So we proceeded to gorge ourselves before continuing on to the campsite. The next day, on the return trip, we looked forward to repeating the feast. But search as we might, we could not find a single worm-free peach. You can draw your own conclusions.

We came home on weekends about once a month, if I remember right, and papa would meet us at Fincastle. Since we usually arrived at night, papa had to make the trip in the dark with only a lantern to light his way. It also was our only light on the return trip. I always felt sorry for papa, because of the lameness his job imposed on him, for having to make these trips. When the trips were in daylight, we were treated to some of the most gorgeous scenery Kentucky had to offer along the railroad. It followed deep green valleys with sparkling creeks, hemmed in with gigantic cliffs. One especially beautiful spot was Kentucky's Natural Bridge, which the railroad had improved to a well-landscaped park.

Before another school year had time to roll around, it became evident that better schooling arrangements must be made than he one just experienced. Mama and papa learned from a fine native gentleman about Berea, and they decided to investigate it, since Donnie and Ralph had to be considered. And so it came about that mama and us children moved to Berea, so we could get the education they wanted us to have, and papa stayed in the oilfield to continue working to support themselves and their ambitions for us. I have always felt a deep sense of sadness because of the role we children played in the breakup of their marriage. Without us to have to consider, they probably would have remained together.

KENTUCKY - BEREA

Don, Ruth, Belle & Ralph Hopkins |

The move to Berea was a transitional period for the family in many ways. Most obviously, it was a cultural transition. Berea is a small town, beautiful by almost anyone's standards. It is essentially a one-industry town, and that industry is Berea College. It's atmosphere was one of quiet culture, and it was wholly dedicated to one ideal - education. The purpose of the College was to extend affordable education to the people of the Appalachian region, and it's different departments covered the entire range of schooling, from the first grade thru a four year college course. The elementary grades formed the Foundation department, the high school grades were termed the Academy, and the College was simply called the College. Besides these, the College maintained the Normal department, devoted to training teachers for the Appalachian region. The College charged no tuition to it's students, but maintained student industries, which produced such things as hand-woven materials, beautiful hardwood furniture, and brooms, among other things. Labor was as much a part of the curriculum at Berea as were the more formal studies, and all students were required to work at least ten hours per week toward meeting their expenses. They were paid nominal wages by the College, to be applied toward their expenses.

The town of Berea maintained a public school thru the eighth grade, and the Academy department of the College took the graduates thru the high school years. I don't know what arrangement the town had with the college to defray the expenses involved, but the relationship between the town and the College was a harmonious one. The student body of all departments of the College formed autonomous enclaves within themselves, and had minimal contact with the townspeople.

Another, and less happy transition for the family in moving to Berea, was the beginning of the end to a united family. There was virtually no work to be had for papa in Berea, so he had to remain in Lee County as long as his job lasted. But at no time, then or later, did he fail to provide for his family, as best he could. Mama, especially, bore a heavy burden, trying to provide shelter and sustenance for her children, while coping with an increasingly serious problem with her left kidney.

When we first moved to Berea, the best affordable housing mama could find was a flat above a shop a stone's throw or so away from the public school. Life was hard for mama there, but convenient for us children. For the first time, Ralph had excellent teachers. Donnie quickly made a lot of friends, and developed here his ability for "horse trading". On one of his trades, he came into possession of a decrepit Barlow knife, and thru a series of trades, wound up with a dismantled bicycle, which he put together, and learned to ride. In all his trades, he somehow managed to make his partner believe that he was getting the better of the deal, and left him feeling happy. Ruth's inclination toward scholastic achievement took form here. My own proclivity toward prowess in spelling reached fulfillment with one of my teachers. She had weekly spelling bees, and I quickly climbed to the top of the line, and held onto it for so long that she had to make a ruling that after two or three times, the head person got demoted to the foot of the class, and had to start over. It usually didn't take me more than one session to work back up to the head of the line. One time the boy next to me tried to bribe me to misspell a word so he could be top boy, but I somehow just couldn't make myself do it. That love for spelling went back to my second grade teacher in the Normal school in Kearney, who singled me out and gave me such a superb start.

There aren't too many happenings from that period of my life that I remember with clarity. One, however, was of two of the huskier boys in the school who used to get on one of the playground swings, facing each other, and pump up momentum until, with one super surge, they would go up and over the top bar. They tried to get me to do it also, but I didn't figure I had the weight - or the guts - to do it, so I declined. They later became daredevil riders on the bobsled and motorcycle riding in a dome. I only completed the seventh grade there, and my teacher persuaded me to take the county exams for graduation that were held in Richmond. I passed them, and so went to the Academy the next year. (Was my teacher just trying to get rid of me?)

Before I pass by those formative years, I should mention my discovery of the College library. In it's basement it had one section devoted entirely to children's books, with "children" broadly defined. It was there I discovered the Rover Boy series, and I read every book in the series. I also read everything I could get hold of that Mark Twain wrote, and as much Greek mythology as I could find. They all helped to color my life.

Around the time I entered the Academy, the family moved to a ramshackle house on the east side of town. It belonged to a friend mama made in the church, and she made it affordable for us. It was two story, with outside plumbing, and we had to get our water from the pump of a house two doors north. But it had a nice woodshed, and a fenced lot where we could raise chickens. The owner had a son my same age, and we became the fastest of friends. While we lived in that house, papa lost his job, because the oil field in Lee County was playing out. Uncle Charlie, aunt Emma and Grandma had left for a new oilfield in Wyoming, so papa came home long enough to size up his chances in Berea, and finding nothing there, tried to persuade mama to move with him to Wyoming. But mama could not have endured another move of that magnitude even if she had wanted to. But she didn't want to; she had assured her children the opportunity for a good education, and adequate medical care for herself. So papa went off to Wyoming alone. Meanwhile, mama had obtained a part-time job as housekeeper for the Churchill family, who had moved to Berea from British India, and established a weaving establishment, The Churchill Weavers, using the high-speed hand looms that he designed and patented. Not too long afterward, mama's kidney problem got so bad she had to go to the hospital and have it removed. The doctor said he almost had to cut her in two to do the job, and there was an anxious week or two when we didn't know whether mama would survive. All the time her only concern was, "what will become of my children?" But she survived, and so did we. Later on, we moved to a smaller one-story house one door north, which also belonged to the widow.

Her son, Louie Gabbard, and I used to have some great times together. We used to go nut hunting in the fall, especially chestnuts, since the blight had not yet devastated them. We used to go swimming together in the creek a mile or so east of town. One time, when the creek was in full flood, we dared each other to jump in, and swim with the turbulent current to a designated point about a quarter mile downstream. And so we did. That was some experience, especially at the end for me. I got temporarily caught in the branches of a small tree that was washing down in the flood.

Another thing I did while we lived there, that I have kicked myself all over the lot and the decades for, was to hunt and break open dozens of what we called "niggerheads", which were prime geodes, and then throw them down after we had looked at the wonderful bowl of crystals they contained. I'd give a lot to have just one of them now.

It was while we lived there also, that I started working in the college broom factory. I understand there is hardly a place in this country now that still manufactures brooms from broom straw. Oklahoma used to be the main region of growth. Now I understand broom straw is imported from Mexico, if at all. Later on I also got a job at Churchill Weavers cleaning up the floors after working hours. Donnie also got a job there later on, and I believe Ruth helped mama take care of their house and children.

Berea Academy, just like the College itself, had the finest, most dedicated staff of teachers obtainable anywhere. They made you want to learn. I loved history and the geography associated with it, partly, I suppose, because the history teacher, Mrs. Elizabeth Peck, was such a wonderful teacher and person. I especially liked English history. But my main interest became chemistry when it became time to take it. The chemistry teacher was Mr. Ambrose, and he knew how to inspire his students, and make it an adventure for them. But during those four years, I sorely needed a father figure to boot me hard and often to make me study the things that didn't really interest me, like Latin and Physics. I found it easy to goof off in mathematical courses, because of the lax manner in which the math teacher conducted his classes. He was a brilliant teacher, but was reluctant to jerk the goofoffs back into line. I have sorely regretted all my shortcomings ever since. Ruth entered the Academy two years after I did, and proceeded to make up in her studies what I lacked in mine. Donnie never did attend the Academy; he went to Wyoming after graduating from graded school. Ralph was still in graded school by the time I graduated from the Academy, I believe.

By the time I graduated, it had been decided that I would join papa in Wyoming. The route I would take would go first to Chicago, where I would visit Uncle Ed in Whiting and Uncle Will in Hammond. I made it to Chicago all right, disembarking at the Illinois Central station, where I was to take a train to Whiting. But with no one to help me, I took the wrong train, which seemed to be going south instead of east. Finally in alarm, I pulled the cord for a stop at the next stopping point, a mere platform alongside the tracks. I wandered down onto the street bordering the tracks, and headed for a street where I saw street cars running. I stopt at a house to inquire what connections I could make for Whiting. It just so happened that the house I stopt at was Uncle Will's house in Hammond. He wasn't there, but Aunt Dessie fed me, and directed me to the proper connections to visit Uncle Ed in Whiting. I had a nice visit with him and his wife, and got my first look at a large body of water, Lake Michigan, while I was there. From Whiting I made my way to the Chicago & Northwestern station in Chicago, where I took the train which would eventually land me in Wyoming.

The trip across Illinois, Iowa and Nebraska was interesting, but uneventful until I reached Chadron, Nebraska, where I was transferred to a typical train for that part of the country - an engine, a half-dozen freight cars, and one passenger car bringing up the rear. Long stretches of the track between Chadron and Lusk, Wyoming were under repair, and the train crept slowly for miles on end. Bored with just sitting, I punctuated it with occasional periods of standing on the rear platform and watching the arid country drift slowly by. Once, when I saw a particularly pretty bunch of wildflowers along the tracks, I got off the platform and picked a handful of the flowers, then raced to get back on the train. As I did so, I heard an unfamiliar roaring sound, and as I caught up with the train I discovered the sound was made by the train passing over a trestle across a chasm which I calculated to be about 150 feet deep. The last several yards of my wild dash were over the ties on the trestle. I stayed humbly on the train for the rest of the journey. The train arrived at Parkerton about ten o'clock that night, and papa was there to meet me with a lantern.

A short piece by Charles Howard Hopkins about life in Kearney,

Nebraska when he was a young boy.

Our Life in Kearney, Nebraska During The Second Decade

Of The Twentieth Century

Kearney was a neat, friendly little rural community, the county seat of Buffalo County. It was served by two trunk railroads, the Union Pacific and the Burlington, and the Lincoln Highway passed thru it. It had an excellent school system, including the State Normal School, where us children thru Donnie attended at least the first grade (more for Ruth and I). Our house was approximately in the northwest corner of town, not far from the Normal school. Besides the house, it had a barn and some outbuildings, for chickens, hogs, and storage space for equipment, wagons, etc. Our transportation was by papa's team of horses (Kit & Fleet), and his work wagon and a lighter "spring wagon". Automobiles were just making their first appearances, more as primitive (and expensive, for that period) playthings. Kearney's main drawback was that it had no industry, and life could be precarious for anyone without an assured job.

Our family's livelihood depended partially on whatever jobs papa could pick up using his team and wagon. But at least equally, it depended upon the garden produce we could raise and store, and upon the income papa was able to gain from the sale of the surplus alfalfa which he raised to feed his horses.

I will devote the remainder of this discourse mainly to picturing the lives or activities of the women in our (extended) family, altho not necessarily to exclusion of the part played by the men. The household work was still traditionally the responsibility of the women, and the dividing lines between women's and men's work were fairly distinct. Appliances for aiding their work were much fewer than what is available today, and many of the ones they had are no longer in use today. They would be considered treasured antiques. Examples of these are the huge cast iron kettles for scalding hogs at butchering time, and the lard press used in rendering the lard. Lighting was done using kerosene lamps and lanterns. Cooking was done on a wood- or coal-burning stove, with a built-in reservoir for heating the water for dishes, cleaning, etc. Washing was a major undertaking. The water had to be heated in a copper boiler on the stove; and the first washing machines and wringers were hand-operated. Much of the dirtiest of the washing had to be done using a washboard. Ironing was an equally woman-killing chore; there were no wash-and-wear clothes then. Many families made their own soap, using waste fat, and either lye or leachings from wood ashes.

One of the women's chores was taking care of the chickens and eggs. They also helped harvest some of the garden produce, altho most of that chore belonged to the men. It did befall them, however, to do most of the preparation of the produce, canning it, drying things like corn and apples, and preserving them by smoking in a special little room with a sulfur candle. At hog butchering time, they fried the sausage (which I believe the men ground up), rendered out the fat and squeezed it out in the lard press, and processed the rest of the meat in the traditional manner. The sausage was formed in balls about the size of golf balls, and packed in lard in big stone jars (which would also be antiques today).

The men tended the larger livestock, but the women performed most of the chores concerned with the milk produced, with the exception of separating the cream from the milk. The DeLaval cream separator required a strong arm and endurance to operate, and the men usually did that chore. The women made butter, using a traditional hand-operated churn. They often sold excess milk and butter to bolster the family finances. The women did most of the grocery buying, planning and preparation of the meals. In that period, many of our groceries were ordered in bulk quantities from Sears Roebuck and Montgomery Ward. We could get items then that are unheard of today, like dried, salted codfish. (Leached, shredded, and mixed with mashed potatoes, then fried, they make good eating, but would surely be looked down upon today).

We had no running water on the premises then, but a pump and an unlimited supply of good quality water for the pumping. The plumbing was outside, which made it pretty rniserab1e in Nebraska's brutal winters.

Naturally one of the main responsibilities of the women was the rearing of their children. The men probably shared that responsibility somewhat more than the men do today. All of us children, I believe, knew the alphabet, knew how to read simple passages, memorized several nursery rhymes, and could tell time before we entered the first grade. They read the familiar Bible stories to us, and made sure we were schooled in the principles of Christianity. They taught us to be proud of the family name we carried, to never do anything to dishonor it, to protect it's (and our own) reputation. They taught us the basic family traditions and values, and inspired us to carry them on.

If this makes it sound like women's lot was endless drudgery, then I must deviate somewhat. Somehow amid all this labor they found time to do such creative things as knitting, crocheting and tatting. Aunt Emma's and Grandma's tatting could hold their own against any lace made anywhere in the world. Grandma's quilting was prize-winning in design and artistic workmanship. All of our women loved flower gardening, or raising flowers in the windows during the cold months. Sewing was not only an artistic outlet, but an absolute necessity. Mama made all her childrens' clothes almost to their teens. Whatever social life the women enjoyed was mostly during impromptu visits with neighbors, and with church groups. Telephones were few, and calling prior to a visit was a formality still unheard of.

That sums up about the most easily-recollected things I remember about that period of our lives. I hope there may be some of it that you will find interesting and useful, as you collect facts and stories about the family.

A short piece by Charles Howard Hopkins about the family's life in Kansas.

Kansas

It was in the Spring of 1917, after school was out, that our family left Kearney to join papa in the oilfield near Eldorado, Kansas. We stopped in Lincoln on the way down to visit with Uncle Walter Boone (mama's brother) and his family. This period of my life comes as near being a blank to me as any, and my memories are not very productive of the kind you are seeking. I guess it was largely because that was the age when I was shedding childhood and about to enter adolescence, and non-boyish matters just failed to register. Possibly also, it was in part because the drabness of the Kansas landscape, its lack of boyish interest, etc. failed to make many lasting impressions. But of the practical, everyday problems of living in that place and time, I will strive to give you my best efforts. You can combine these with the previous writing on this period which I sent to you, but which contained all too little of the kind of information which you are seeking.

Papa didn't send for us to join him until the Company had built a house of sorts for us. He had been living in the tent which he took down in his wagon. One of the bad things that happened to him during that period was that while he was on duty, someone rifled his tent and stole his precious collection of Indian arrowheads, hammers, and other artifacts that he had collected while plowing the fields of Indiana and Nebraska.

Kansas oil field houses |

I don't remember much about the house the Company provided for us, whether it was three-room or four-room, but certainly not more than that. It was inadequate even for the pared-down belongings we had kept, and papa erected the tent adjacent to the back of the house to take care of the overflow. During the first of the two tornados we survived there, mama went into the tent to try to secure it more strongly when the wind rose, and it collapsed the tent, and the center beam fell on mama's head and nearly knocked her out.

Mama had had surgery on her left kidney while we were in Kearney, and still had a tube draining the urine from that kidney in her left side. (She would not be free from it for many years, when she had to have the kidney removed in Berea). That condition was a great handicap to her in trying to perform her daily chores, but she somehow persevered. It was necessary to wear a diaper-like pad over the tube, and it had to be changed several times daily, and washed and dried. I don't remember what our laundry facilities were at the time, but I'm sure they were minimal. Water was also a problem, as it always is in a new oilfield (and the old ones too). I don't know what the source for our water supply was there, but it was very hard, as that was limestone country.

Of all the things that seemed to bother mama most, it was the incessant wind. The state of Kansas is truly "Tornado Alley". We survived two tornados there. Other than bringing down our tent, no other damage was done to our house. But the wind picked up the house next to ours and set it catty-cornered on its foundation. It also felled a forest of derricks thruout the field.

Eldorado was several miles from where we lived, and was the only available source for groceries and all the other staples of life. There were no country stores, and getting the necessities depended on the availability of transportation into town. That's where any medical help was located also. There were no churches in the oilfield, and initially no school. One was erected in time for opening near the onset of Winter; but after a short time of operation, the great flu epidemic shut it down.

With the war winding down in 1918 it became apparent that it would not be necessary to operate the field at its former rate, and layoffs began. Papa, Uncle Charlie and Uncle Will were working under a foreman named McDermott, and when the company announced his transfer to a new field that was opening in Lee County, deep in the mountains of eastern Kentucky, he promised all three of them that if they cared to follow him there and apply for work, he was fairly sure he could find jobs for them. That meant that the family would have to split up again, as no housing existed as yet for them. So mama and papa had to find some safe haven for her and us children until papa was in a position to send for us.

Mama's stepmother (whom I'm not sure mama had ever met) was running a small boarding house in her rather spacious home in Ft. Wayne, Indiana. Mama's sister, Aunt Hazel and her half-brother George, were living in the house. I don't know, but I imagine mama was able to arrange thru Aunt Hazel that her step-mother would accept our family as boarders until the school year was out the following Spring. But however it occurred, that is where mama and us four children lived in the interval between the Eldorado oilfield and life in the oilfield deep in the mountains of Kentucky.

ADDITIONAL DATA ON THE HOPKINS FAMILY,

MOSTLY DRAWN FROM MEMORY

Going back to the basic family of Barkley Brown & Mary Ann Hopkins, I will try to tell you what I actually know about them and their movements, and will give you my best guess on what I can deduce from what I actually know. Fair enough?

Grandpa Hopkins died at the age of 75, presumably in Montpelier, Indiana. The family was probably scattered by then; papa was living in Kearney, Nebraska. Some of the sons worked in the early oil fields of Indiana, and possibly Ohio and Illinois, but I don't know the location of any of these early fields. Uncle Ed, the oldest, became employed in the Standard Oil refinery in Whiting, Indiana in its early days, when refinerys were still pipe stills, and remained with them until his retirement. He had one son, Carl, whom I met when I visited Uncle Ed on my way to Wyoming. I'm not sure when Uncle Will started working in the oil fields, but I believe he worked in the field near Nowata, in Oklahoma prior to WW1. When the great Eldorado, Kansas oilfield opened up, he established his family there. Aunt Alice married a rough oilfield worker, presumably in Indiana, and they moved into the Texas oilfields rather early (his name was Stephens). They were also drawn to the Eldorado oil field. I don't know much about Aunt Emma's life prior to 1917, except that she visited us in Kearney while papa was still there. I recall family members saying that she worked in a boarding house in Nowata during the oil boom there, but I don't know whether Grandma lived with her then or not (Grandpa died in 1914). Presumably she followed Uncle Will, with Grandma, to Eldorado. After Uncle Charlie graduated from high school, he spent some time working on an irrigation project near Sheridan, Wyoming. I presume that is about the time he bought that quarter-section of land in North Dakota. Anyhow, he joined Aunt Emma and Grandma, either in the Eldorado oilfield, or shortly before that time. Then when papa brought our family to Eldorado, a goodly section of the Hopkins family were together - Grandma, Aunt Emma, Aunt Alice, Uncle Will, Uncle Charlie and Papa. Not accounted for in this reunion was Uncle Luther. He seemed to have gone to the oilfield around Lawrenceville, Illinois soon after departing the Indiana oilfields, and stayed and raised his family there.

After the Eldorado oil field began playing out, the family scattered, and has never gotten together to that extent again. Aunt Alice and Uncle Jim returned to a Texas oilfield. Uncle Will, Uncle Charlie and Papa found new jobs in a new oilfield deep in the mountains of Lee, County, Kentucky. When that field began to play out, Uncle Will left and settled in Hammond, Indiana, if I'm not mistaken. What he did I don't know. Uncle Charlie, Aunt Emma and Grandma left for an oilfield at Parkerton, Wyoming, and eventually papa followed them there. During his last years in Lee County is when our family started to break up. That's because there were no schools there, and mama had to take us to Berea where there was good schooling. When papa left Lee County, there was no chance for him to make a living in Berea, so he did what he had to, to continue to make a living for his family. The family gradually fell apart after that. But I don't fault either mama or papa; she continued to be a good mother, and he continued to be a good father and provider for his family.

In reference to your observation that a handwritten notation, presumably in my handwriting, refers to family records dating back to 1425: I don't have any copy of such an entry in the record I have, and if there is such a record it may be in the vast amount of heraldic material Bob provided. I don't have time to look for it right now, but 1 believe you have a copy of the same material, so you might try it. I do not know why Benjamin and Sarah Hopkins sent their son to Elizabeth Haddon in America, but I imagine it was because they wanted him to grow up in a freer environment than was possible in London. Then also, John Estaugh already owned the land that Elizabeth went to care for, and they might have had in mind part of its inheritance going to their son.

I must admit (blush, blush) that, although I have known about Long fellow's poem "Elizabeth" for a long time, I have never read it. I intend doing that yet.

I have long been appreciative of the enormous contributions the Quakers have made to the structure of American life. One need only read the Constitution and examine our judicial system to get some idea of those contributions. The Quakers' living principles form the bedrock of our American values, much more than those of any other group, including the Pilgrims and the settlements in Virginia. It is true that some of their customs and beliefs were considered weird by non-Quakers, exposing them to public ridicule and internal revolt. Their eccentricities eventually caused the movement to self-destruct to a great extent, but their ideals live on in our basic American ideals. I believe Grandpa and Grandma simply revolted at the more extreme customs of the church, rather than for any other reason for leaving it. I agree with you that their belief that each person has within him (or her) an Inner Light, but I disagree that a church doesn't need a minister. Every group has to have a leader; without one, the "every-man-for-himself" attitude would prevail, and organization and progress would be inhibited or missing entirely.

That is all for this time. I must stop and get this in the mail and prepare dinner. We baked the pumpkin pies this morning.

REMEMBRANCES OF THE HOPKINS FAMILY AND THE TIMES IN WHICH THEY LIVED.

That portion of the Hopkins Family about which we are concerned 1s the family of Barkley B. and Mary Ann Hopkins and their offspring. and especially of their son Arthur H. and Belle B. Hopkins.

My grand parents, Barkley B. & Mary Ann Hopkins, lived and raised their family on a farm near Montpelier or Pennville, Indiana. My father, Arthur H., said he never got beyond the third or fourth grade in schooling, since his help was needed on the farm to help the family get by. I don't know at what age, or under what circumstances he was able to break away from that necessity, but I do know that their family ties were exceptionally strong, and remained so as long as any of them lived. All I know about his life prior to his marrying mama is that he had some experience in the early oil fields in Indiana, and that he participated in the land run at the opening of the Cherokee strip. He wasn't impressed, apparently, and returned to Indiana.

I know little about his and mama's courtship and marriage. His reason for going to Nebraska was to work and save in order to buy a farm of his own. Land was still plentiful and reasonably cheap yet in Nebraska, and it seemed like the land of opportunity to him, I suppose. Farming was such an essential part of him. I believe Helen was born in Indiana, but I'm not sure. He was working on a farm above G1bbon in Buffalo County, trying to save enough to invest in a farm of his own. I was born there, and then Ruth. Mama began having serious health problems there, and he finally gave up and moved to Kearney where mama could get the medical help she needed. I am sure mama and papa went by train from Indiana to Nebraska. Papa was the only member of his family to move to Nebraska. When other family members came there, it was only to visit. In previous writing, I described a few of the happenings in our lives in Kearney, which you can refer to. They were all too brief; but maybe I can embellish them somewhat if you would care for me to, and tell me what you would most like to know. I was nine when I left there, and my memory of details you might be most interested in is all too short. When things got too bleak in trying to make a living there, he went alone down to Kansas, to the great Eldorado oilfield, where his family was already well-established. Uncle Will, Uncle Charlie, Aunt Emma, Grandma, Aunt Alice and her family were already there, and helped papa get a job there. He hitched up his team of horses to his wagon, took a tent and what clothes and provisions he could, without leaving the family destitute, and drove to Eldorado. He took our dog, Trixie, with him for company. He said he suffered more on that trip than at any time previously in his life. He lived in a tent until the company provided him with a "house," and then he sent for his family. We traveled by train.

It was while we were in the oilfield that the great flu epidemic hit. Every member of the extended family came down with it, except him. He had the whole family to care for besides his job.

And now, to back-track a little. You asked about what I remembered about my grandpa Hopkins. Unfortunately, very little. He and grandma visited us in Kearney, and I remember him as a smallish white-bearded man with a chronic case of bronchitis. He later died from it in Indiana. As to his personal characteristics, I know little, except that he had worked hard all his life, and did the best he could for his family.

As oil production dwindled in the Eldorado field, it was inevitable that most of the workers would sooner or later have to find other work in other areas. Papa, Uncle Charlie and Uncle Will had an Irish foreman named McDermott who knew good men when he saw them. The company transferred him to the new oilfield developing in Lee County, Kentucky, and he promised all three of them jobs there if they would come there and apply. Both Uncle Charlie and Uncle Will went as field foremen, and the company promised houses for them when they arrived. But papa went as a pumper with a promise of a house later. That is why he had to arrange for his family to go to Ft. Wayne, Indiana where mama's stepmother ran a small boarding house, and had agreed to take us in until the school year was over. Papa stayed with Uncle Charlie, Aunt Emma and Grandma until his house was ready, and then sent for us. In papa's move from Kansas to Kentucky, he leased a boxcar, into which he put his team of horses, his belongings, and himself, and that's how he moved to Kentucky. Our moves, of course, were by train.

As you surmised. life in the oilfield camps was indeed hard for the women. It was especially hard for mama, who already had a drainage tube from her left kidney protruding from her side. The "house" that was provided for us there was down to basics, and the less-essentials were stored in a tent behind the house. In the wet seasons mud prevailed. In the dry seasons, scorching heat with no relief had to be endured. The winters were always brutal. Water for household use was always a problem. The niceties we take pretty much for granted were nearly non-existent, and social life was occasional visits between friends. Good schools were seldom available at the out-of-way places where oil fields usually were found. Medical facilities were whatever the nearest town could provide, which was usually minimal. Does that give you a picture of what it was like for the women? But to their everlasting credit, they were by and large as hardy a breed as their men, and made the best of the circumstances under which they found themselves.

Notes:

These pieces were written by my father, at my request, starting in March of 1991. I wanted to preserve his story and the story of our family for the future. He wrote these pieces over a period of several months.

These pieces are invaluable to me for two reasons. First, because they give eye-witness accounts about life as he lived it, and as we'll never know it again. Secondly, and more importantly, they tell a lot about him as a man. I think anyone reading these pieces will get a good idea of the character of my Father, and understand the loss I feel because he's gone.

In reading these pieces, you've probably noticed that my Father had his own spelling rules. He wrote thot instead of thought, brot instead of brought, etc. He was very much an individual, in spelling as in other aspects of his life.

I've added links to photos which illustrate the people and the places my Father describes. Most of these photos came from his Uncle Charley, but one came from our Abraham cousins in Kansas.

Back to Charles Howard Hopkins page Howard Hopkins' Centennial page More about the family in the oil fields

This file was last updated on 7/15/2019.

| Home | Contents | What's New | Myself |